When driving 5 mph over the 65mph speed limit on Orange County freeways, I notice many motorists passing me. This occurs so often I’ve concluded that most people are “speeders”, that is, in technical violation of the traffic laws. Not surprisingly, society has felt it necessary to create a separate term for people going far over the speed limit—say 125mph. Those are often labeled “reckless drivers”. You might say that speeding 5mph over the limit is less wrong that going 60mph over the limit. The financial penalty is certainly much lower.

There are many areas, however, where society has decided to extend the same pejorative term over a wider set of infractions. This is usually done to impress upon the public that the relatively milder infraction is also really, really bad. At the end, I’ll consider an example of the opposite—creating a softer term for something that seems (objectively) just as bad. I’ll also focus on society’s view of the situation, not my own. Please try to keep that focus in the comment section.

Here are some terms that have been extended over an increasingly wide range of situations:

Genocide: Most people believe that genocide in the sense of destroying a culture is less wrong than genocide in the sense of mass murder.

Segregation: Most people believe that de facto segregation is less wrong than de jure segregation.

Slave Labor: Most people believe that slave labor in the sense of exploitation of migrant workers is less wrong than chattel slavery.

Pedophilia: Most people regard sex with a teenagers as being less wrong than sex with a young child.

Rape: For a given age, most people believe that statutory rape is less wrong than forceable rape.

Homelessness: Most of America’s homeless live in shelters such as motel rooms. But most people regard living on the street as being worse than living in a motel.

Drunk driving: Most people believe (at least implicitly) that driving a with a blood alcohol level of 0.10% is less wrong than driving with a blood alcohol level of 0.20%. (BTW, the legal limit was 0.15% when I was young, now it’s 0.08%.)

Child labor: Most people view having 14-year old children working is less wrong than having 8-year old children work.

Child abuse: Most people believe that spanking a child is less wrong than intentionally injuring a child.

Racism: Most people believe that unequal outcomes, aka “structural racism” is less wrong than intentional discrimination against minorities.

In the comment sections, I noticed that many people struggle with nuance. If you say X is less wrong than Y, you are seen as saying X is “perfectly OK”, or “not a problem at all”. Thus, people seemed surprised by my claim that even after the recent crackdown, the situation in Hong Kong is still much better than on the mainland.

In fact, that claim should not have been even slightly controversial. And yet people conflate the true claim that “bad things have recently been done to Hong Kong”, with the false claim that “things in HK are just as repressive as on the mainland.”

A recent FT story about Hong Kong University illustrated both the negative:

Academic freedom has shrunk, many say. Several of its academics have been attacked by Chinese state-backed media outlets in Hong Kong. US human rights law academic Ryan Thoreson, who was hired by HKU, was denied a visa in 2022.

and the positive:

The total number of students at HKU, meanwhile, has increased from 29,099 in 2018 to 42,330 in 2025, with the proportion of mainland Chinese students studying under government-funded programmes rising from about 15 per cent to 24 per cent during the period.

Many mainland Chinese people who studied abroad come “to HKU for [its] western education,” said a HKU social sciences lecturer. “They don’t want us to tell them [the] Chinese party line or propaganda . . . [in that sense HKU] maintains a competitive edge.”

The world is complex. It can be true that Hong Kong has gotten worse in several important ways, while also being true that Hong Kong is still freer than the mainland in many other important ways.

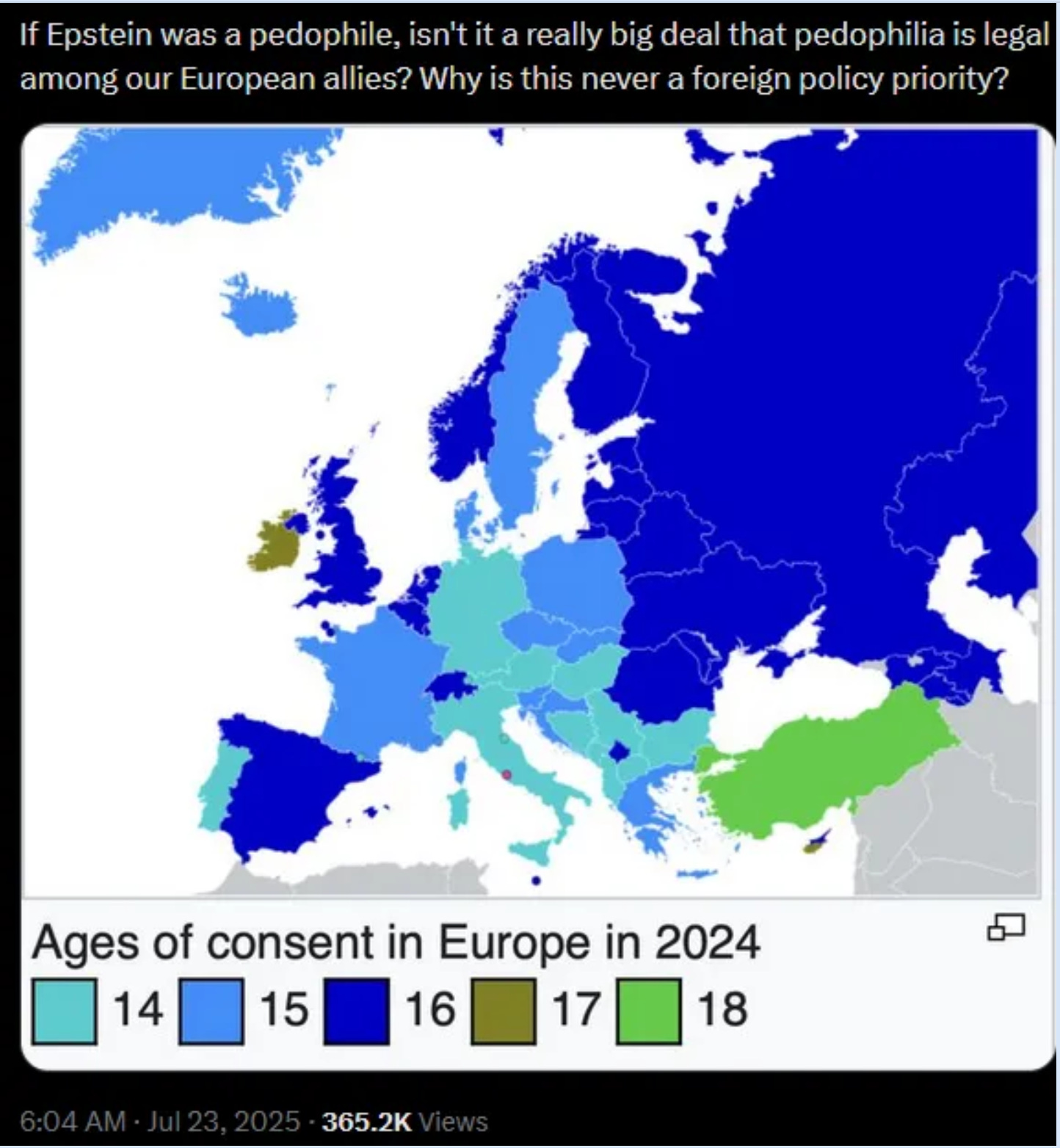

Scott Alexander directed me to an interesting tweet by Richard Hanania:

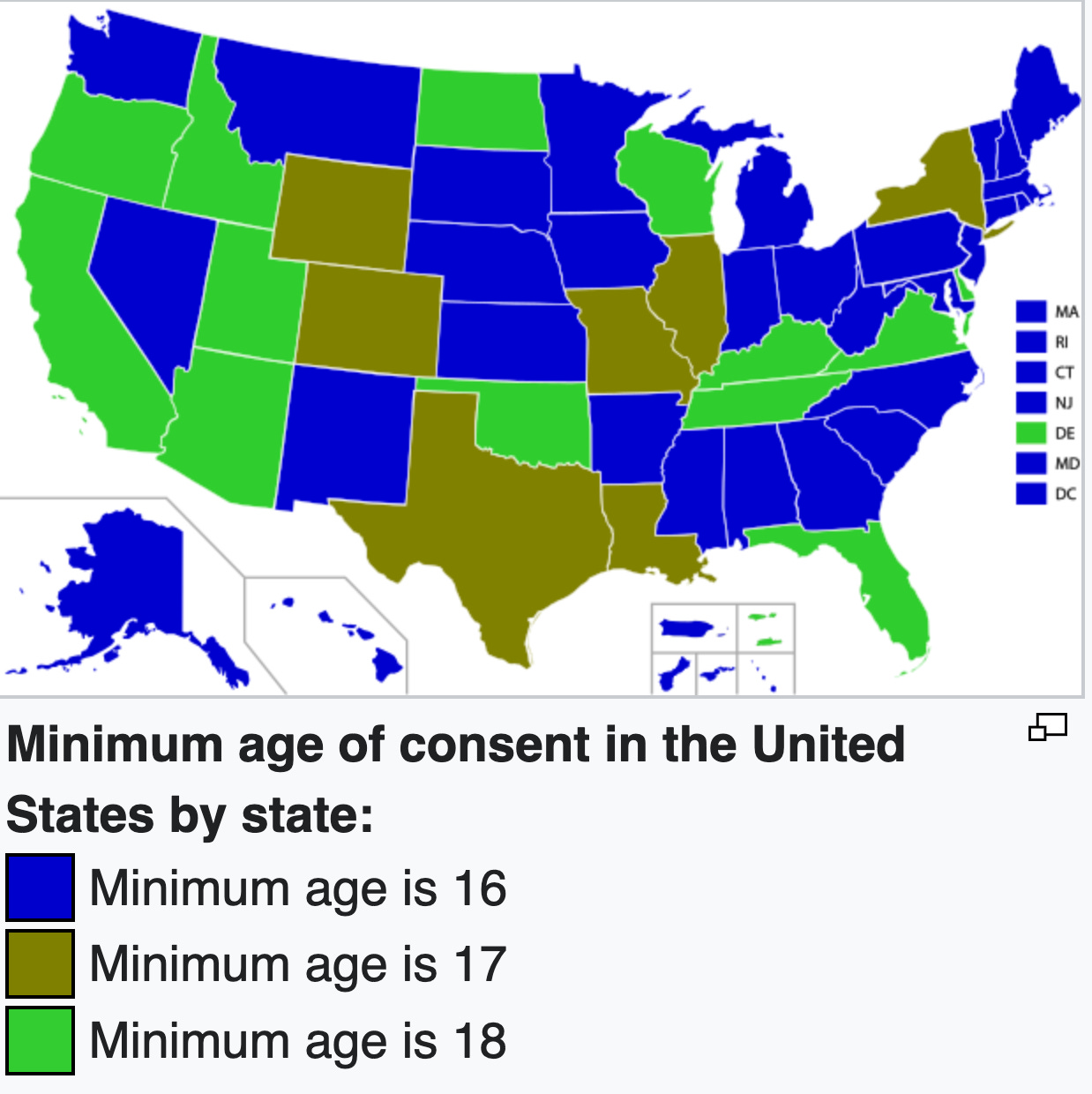

According to Wikipedia, the age of consent is roughly two years higher in the US (16-18) than in Europe (where it is 14-16):

More surprising to me is the fact that the differences seem sort of random, not correlated with cultural differences in the way that I would have expected. Norway aligns with Spain, Germany aligns with Portugal, Sweden aligns with Greece, etc. And the same sort of seemingly random pattern occurs throughout the US.

Alexander comments on Hanania’s tweet:

I think there’s a boring answer, where the law is more complex than just a single number and whatever kind of weird trafficking Epstein was doing is worse than whatever normal relationships these European laws are permitting. But assuming that there’s a substantive difference even after taking that into account, I think my answer is something like - we’ve got to divide kids from adults at some age, there’s a range of reasonable possible ages, we shouldn’t be too mad at other societies that choose different dividing lines within that range - but having decided upon the age, we’ve got to stick with it and take it seriously (in the sense of penalizing/shaming people who break it). This is more culturally relativist than I expected to find myself being, so good job to Richard for highlighting the apparent paradox.

That’s a reasonable take, but I suspect there’s more that could be said on the subject. For instance, spanking is allowed in the US but banned in many European countries. So there does seem to be a real cultural difference regarding the question of how best to “protect kids”. Put simply, Europeans seem more horrified by violence and Americans seem more horrified by underage sex. And yet the difference is not absolute—it’s a matter of degree. Europe does have age of consent rules, and America does ban excessive violence against children.

When questionable behavior occurs along a sort of continuum, there will naturally be differences as to where to draw the line. And those differences are not just regional, they also occur over time. During my lifetime, I’ve seen many of the terms listed above extended over a wider range of situations. At the same times, terms like adultery, sodomy and promiscuity have lost a bit of their sting.

When a pejorative is extended over a wider range of situations, there is generally a policy agenda hovering the background. Proponents of the extension would argue that there is increasing awareness of the harm done by various types of behavior, and the use of a pejorative term for even milder forms of wrong behavior has real social utility. It’s a sort of wake-up call. “You may think there’s nothing wrong with driving home from a bar while slightly inebriated, but people die almost every day because of that sort of behavior. That’s why we need to categorize a blood alcohol reading of 0.10% as drunk driving.”

Unlike with drunk driving, I’m not aware of any major changes in America’s age of consent laws during my lifetime. Nonetheless, I would argue that the extension of the term “pedophile” from those having sex with young children to also include those having sex with teenagers has effectively changed the public policy, making it at least slightly more restrictive due to what Alexander calls “shaming.”

Indeed, most of the terms that I listed above have been extended to a considerably wider range of activities than when I was young. In at least one case (racism), a backlash has recently begun, and there’s now some pushback against the concept of “structural racism”.

Why is word choice so effective in public policy debates? I think it goes back to the lack of nuance that I noticed in response to my China post. Many people have trouble understanding that if X is really bad, and Y is a little bit like X, that does not imply that Y is really bad. It might still be wrong, but considerably less wrong. Or it might not even be wrong at all.

Very few people would wish to defend things like genocide, slave labor, racism, and pedophiles preying on children. Thus, if you can successfully extend the definition of these terms to a wider range of activity, you can discourage people from pushing back against your policy agenda.

Defenders of the definitional change would argue that it provides a sort of wake-up call. Go back to this comment by Alexander:

whatever kind of weird trafficking Epstein was doing is worse than whatever normal relationships these European laws are permitting.

I suspect that Alexander is alluding to the fact that people tend to have a more accepting view of “Romeo and Juliet” situations than they do of older men preying on younger girls. Those who defend broadening the definition of pedophile presumably see this as a sort of wake-up call to society—stop romanticizing young love.

[Note: The term pedophile has an ambiguous meaning in one other respect. At times it refers to behavior, while at other times it refers to a psychological profile. In this post I am referring to behavior.]

Thus far we’ve considered using the same term for situations that are quite different, at least as a matter of degree. But the opposite situation can occur when society is trying to create distinctions regarding seemingly equivalent activities. The connotation of escort is less negative than prostitute, and not just regarding sex. You can “escort” someone to the party, but you “prostitute yourself” by being paid to advocate policy views that you do not actually hold.

Both escorts and prostitutes provide paid sexual services for money. But escorts are generally seen as being more discreet. The use of a different term may relate to the fact that much of society worries more about prostitution as a social blight on our streets, than about the abstract concept of sex for money. Is it prostitution if a billionaire gives a woman a diamond neckless at dinner, and she later sleeps with him? In many cases, our ethical intuitions are difficult to codify into law.

The prostitution taboo might also help us to better understand laws regarding underage sex. Drunk drivers often go to prison, while less severe driving infractions result in a fine. But (AFAIK) there are no fines imposed on borderline cases of underage sex. It’s either “that’s perfectly OK” or “prison for you”. I suspect that’s because having a man pay a fine for slightly underage sex would remind people too much of prostitution.

This post is subtitled “using words as weapons”. Is a weapon a bad thing? I’d say it is a good thing if in the hands of a Ukrainian soldier and a bad thing if in the hands of a Russian soldier. Some definitional changes probably have positive effects while others have negative effects.

But I also see some value in precision, having more terms rather than fewer terms. Thus, I often see people refer to China’s activities in Xinjiang as “genocide”. Presumably they are using the “cultural genocide” definition. But then I see people claim that today’s China is like Nazi Germany, which seems kind of ridiculous. Is the more expansive use of terms like genocide impacting the way that we view the world?

While I won’t deny that the wake-up call aspect of an expansive definition may have value in selected cases, I believe we are generally better off in the long run with a more precise use of language.

If we lived in a world full of people like Richard Hanania and Scott Alexander, then things would be much simpler. “You say the bombing of Hiroshima was an act of terrorism? That’s obvious. We were trying to terrorize the Japanese public into doing what we wanted—surrender. Now let’s discuss whether it was justified terrorism or unjustified terrorism.” Or “You say taxation is theft? Fine, now let’s discuss whether it is OK for the government to steal by taxation.” Or “Indentured servitude is slavery? The military draft is slavery? You say that like it’s a bad thing.” (I use quotation marks because I don’t agree with all of those imaginary claims.)

But we don’t live in a world of rational people. We live in a world where words have an almost mystical power. To the average person, successfully labelling something “terrorism” or “theft” or “slavery” is enough to shut down debate. To the average person, these things are wrong by definition. In our world, those who define words get to determine public policy.

PS. I was thinking of entitling this post “Defining Deviancy Up”, but then I thought about how few of my readers would even be old enough to remember Daniel Patrick Moynihan.

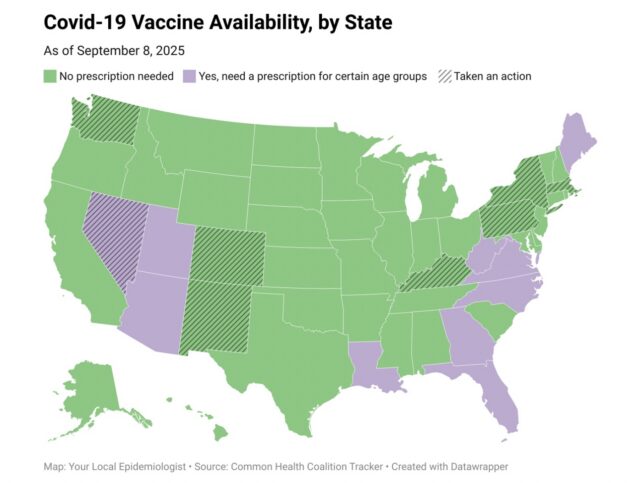

The map provides an overview of COVID-19 vaccine availability and actions for access<br />by state.

Credit:

The map provides an overview of COVID-19 vaccine availability and actions for access<br />by state.

Credit: