Earlier this week, Ars spent some time driving the new Nissan Leaf. We have to wait until Friday to tell you how that car drives, but among the changes from the previous generation are door handles that retract flush with the bodywork, for the front doors at least. Car designers love them for not ruining the lines of the door with the necessities of real life, but is the benefit from drag reduction worth the safety risk?

That question is in even sharper relief this morning. Bloomberg's Dana Hull has a deeply reported article that looks at the problem of Tesla's door handles, which fail when the cars lose power.

The electric vehicle manufacturer chose not to use conventional door locks in its cars, preferring to use IP-based electronic controls. While the front seat occupants have always had a physical latch that can open the door, it took some years for the automaker to add emergency releases for the rear doors, and even now that it has, many rear-seat Tesla passengers will be unaware of where to find or how to operate the emergency release.

A power failure also affects first responders' ability to rescue occupants, and Hull's article details a number of tragic fatal crashes where the occupants of a crashed Tesla were unable to escape the smoke and flames of their burning cars.

China to the rescue?

In fact, the styling feature might be on borrowed time. It seems that Chinese authorities have been concerned about retractable door handles for some time now and are reportedly close to banning them from 2027. Flush-fit door handles fail far more often during side impacts than regular handles, delaying egress or rescue time after a crash. During heavy rain, flush-fit door handles have short-circuited, trapping people in their cars. Chinese consumers have even reported an increase in finger injuries as they get trapped or pinched.

That's plenty of safety risk, but what about the benefit to vehicle efficiency? As it turns out, it doesn't actually help that much. Adding flush door handles cuts the drag coefficient (Cd) by around 0.01. You really need to know a car's frontal area as well as its Cd, but this equates to perhaps a little more than a mile of EPA range, perhaps two under Europe's Worldwide Harmonised Light vehicles Test Procedure.

If automakers were that serious about drag reduction, we'd see many more EVs riding on smaller wheels. The rotation of the wheels and tires is one of the greatest contributors to drag, yet the stylists' love of huge wheels means most EVs you'll find on the front lot of a dealership will struggle to match their official efficiency numbers (not to mention suffering from a worse ride).

China's importance to the global EV market means that, if it follows through on this ban, we can expect to see many fewer cars arrive with flush door handles in the future.

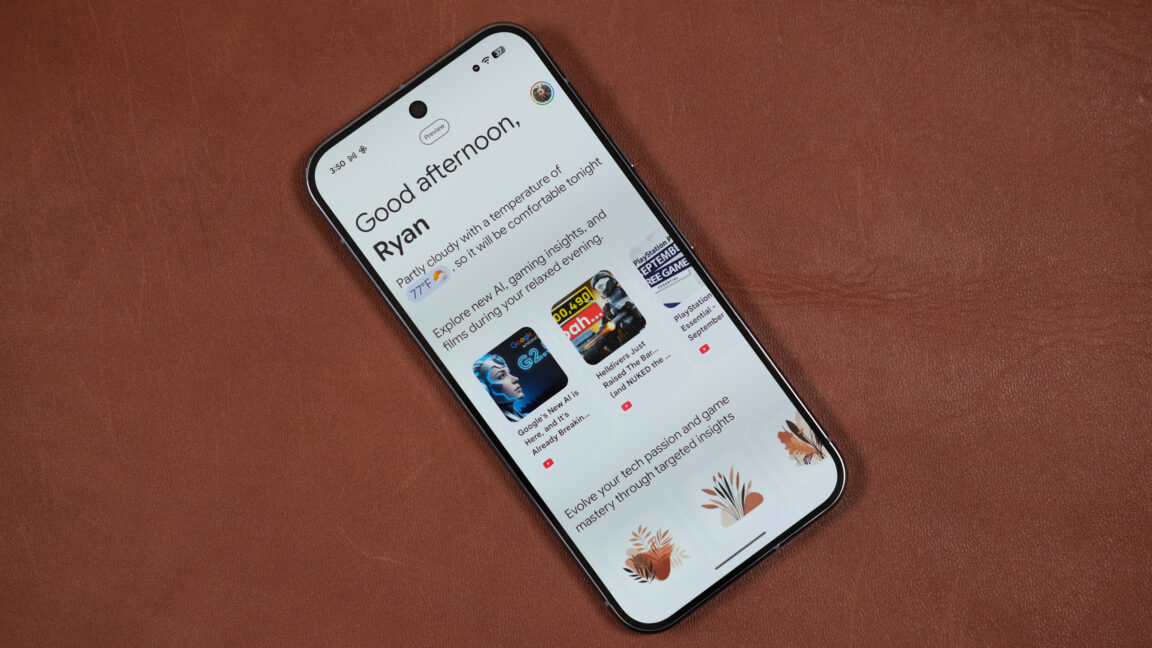

Google is one of the most ardent proponents of generative AI technology, as evidenced by the recent launch of the Pixel 10 series. The phones were announced with more than 20 new AI experiences, according to Google. However, one of them is already being pulled from the company's phones. If you go looking for your Daily Hub, you may be disappointed. Not that disappointed, though, as it has been pulled because it didn't do very much.

Many of Google's new AI features only make themselves known in specific circumstances, for example when Magic Cue finds an opportunity to suggest an address or calendar appointment based on your screen context. The Daily Hub, on the other hand, asserted itself multiple times throughout the day. It appeared at the top of the Google Discover feed, as well as in the At a Glance widget right at the top of the home screen.

Just a few weeks after release, Google has pulled the Daily Hub preview from Pixel 10 devices. You will no longer see it in Google Discover nor in the home screen widget. After being spotted by 9to5Google, the company has issued a statement explaining its plans.

"To ensure the best possible experience on Pixel, we’re temporarily pausing the public preview of Daily Hub for users. Our teams are actively working to enhance its performance and refine the personalized experience. We look forward to reintroducing an improved Daily Hub when it’s ready," a Google spokesperson said.

It's not surprising that Google has hit pause on Daily Hub. Google's approach to mobile AI relies on the Tensor processor's capable NPU. Pixel phones process your personal data on-device rather than sending it to the cloud, which is how Daily Hub is supposed to glean insights into your life. The problem is that it doesn't do that very well.

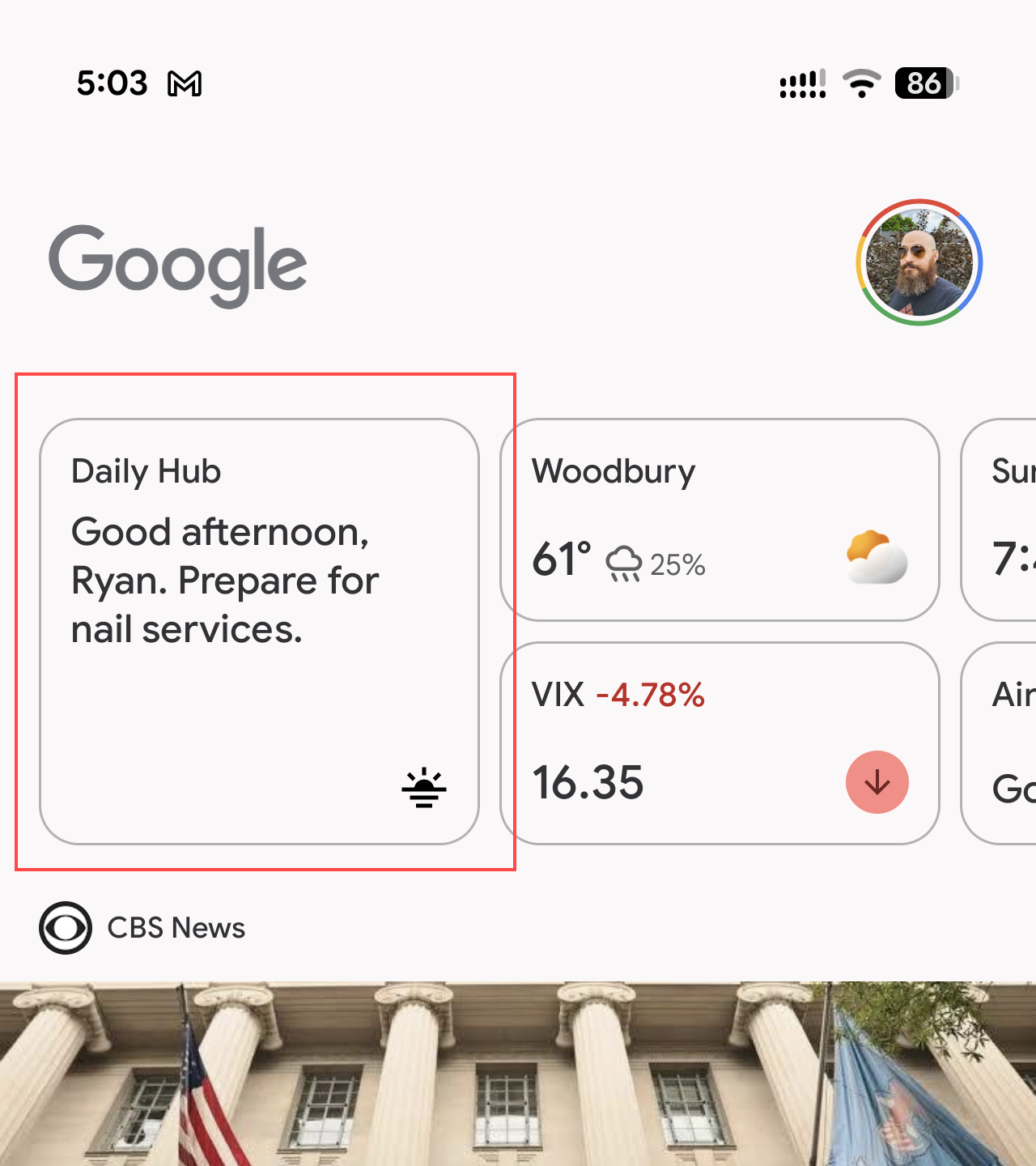

Daily Hub wasn't smart enough to understand the "nail services" were on my wife's shared calendar.

Credit:

Ryan Whitwam

Daily Hub wasn't smart enough to understand the "nail services" were on my wife's shared calendar.

Credit:

Ryan Whitwam

As we mentioned in our review of the Pixel 10 series, Daily Hub's premise is similar to Samsung's Now Brief. They both pull in data from your apps and run it all through on-device AI models to create a digest of your life that is refreshed multiple times per day. Samsung has continued promoting Now Brief as its chief AI innovation despite the fact that it rarely offers more than the weather and calendar reminders. Google's Daily Hub was in a similar place, but it may have been even less useful.

In our testing, Daily Hub rarely showed anything beyond the weather, suggested videos, and AI search prompts. When it did integrate calendar data, it seemed unable to differentiate between the user's own calendar and data from shared calendars. This largely useless report was pushed to the At a Glance widget multiple times per day, making it more of a nuisance than helpful.

Smartphones are overflowing with personal data, which is one of the reasons they are such attractive targets for hackers. Despite this, both Samsung and Google have found little success generating useful daily insights with on-device AI models. We wait with bated breath to see if Google can make Daily Hub worth using when it returns.

I marked my 8-year anniversary this week of Techtonic, my radio show and podcast at WFMU. The episode, called “Milestones for Big Tech... and Techtonic” (see episode page / downloadable podcast), began with a brief acknowledgement of the anniversary. And that was the end of the good news, as I then proceeded to relate what has been happening in tech.

The headline, if I had to summarize the major developments of the past two weeks, is that the Big Tech CEOs have reached a new stage where they can act with impunity, breaking antitrust laws and cozying up to authoritarians, all without facing any consequences. We’ve reached a moment, not seen since the Gilded Age a century ago – and perhaps never before, at this scale – in which a tiny group of ultra-powerful people no longer face any guardrails. And they know it. Let’s name it: oligarchs achieving escape velocity.

In rocketry, escape velocity is the speed that allows an object to escape Earth’s gravity. Once you hit 25,020 miles an hour (40,270 km/h), you’re free to head wherever you like in the solar system. In the same way, the Big Tech companies are slipping the surly bonds of regulation, democracy, and ethics altogether.

See, for example, Google’s stunning victory in the giant antitrust lawsuit brought by the Department of Justice for the company’s long track record of anticompetitive behavior. After having been determined a monopoly, and after having been shown to act illegally in the preservation of that monopoly, on September 2 Google was finally assigned a remedy – of almost nothing.

As Matt Stoller put it, “this decision isn’t just bad, it’s virtually a statement that crime pays.” Brian Merchant called it a “disaster.”

Cory Doctorow explained:

Let’s start with what’s not in this remedy. Google will not be forced to sell off any of its divisions – not Chrome, not Android. Despite the fact that the judge found that Google’s vertical integration with the world’s dominant mobile operating system and browser were a key factor in its monopolization, Mehta decided to leave the Google octopus with all its limbs intact.

Google won’t be forced to offer users a “choice screen” when they set up their Android accounts, to give browsers other than Chrome a fair shake.

Nor will Google be prevented from bribing competitors to stay out of the search market.

This means Google can continue its bribery of Apple: it’s been paying Apple around $20 billion per year to make Google the default search engine on Apple devices, thereby subjecting Apple users to Google’s surveillance, while squeezing out alternative search engines, and – just as importantly – keeping Apple from developing a search of its own.

Now Google has carte blanche not only to keep up its monopolistic behavior, but find more ways to exploit everyone else.

Escape velocity.

Yet even the antitrust news wasn’t the most disturbing sign of Silicon Valley dominance in the past week. On Sep 4, 2025, Big Tech CEOs descended upon the White House to join the current occupant for an oligarchs’ dinner party. This included Bill Gates (Microsoft founder), Tim Cook (Apple CEO), Safra Katz (Oracle CEO), Sam Altman (OpenAI CEO), Sergey Brin (Google founder), Sundar Pichai (Google CEO), and Mark Zuckerberg (Facebook/Meta CEO). On Techtonic I played this clip of those billionaires’ remarks, profusely thanking the current occupant for his “leadership.” (Pointedly, Sergey Brin thanked him for “supporting our companies instead of fighting them” – a veiled reference to the antitrust decision from a few days before – as though exposing his company’s flagrant behavior counts as “fighting” Google.)

Sergey is right about one thing, which is that there is a fight to be had. As I said on the show, the challenge ahead of us isn’t primarily about left versus right but about Big Tech versus the rest of us. About authoritarianism vs. democracy. About a tech industry that serves a handful of billionaires vs. technology that creates widespread good in society. The dinner table on Thursday night was full of people who have chosen their side.

Two days later, the We Are All DC protest filled the streets of Washington, DC with thousands of protesters, chanting “free DC,” in response to the current occupant’s militarization of the city. This is the same occupant who has ordered kidnappings in broad daylight, with masked men forcing civilians into unmarked vehicles. As I wrote in AI is creating a frictionless surveillance state, this is done with the help of Big Tech tools – and now, we can see, it’s with the full and enthusiastic support of the CEOs. They’ve chosen their side.

The truth is that technology can make things better. And tech companies can be stewards of these tools, helping citizens and communities flourish, while – yes – building profitable businesses. It’s just exceedingly hard to achieve those goals in an environment dominated by growth-at-any-cost Big Tech companies enjoying the absence of any meaningful regulation.

Jonathan Kanter, assistant attorney general for the antitrust division at the Department of Justice from 2021 to 2024, put it well in a September 7 essay in the NYT (here’s a gift link) called “Why Google Got Off Easy”:

My disappointment is not just that Google was not properly held accountable, for the stakes extend beyond this particular case. If companies can flout the rules, reap trillions of dollars and face only modest constraints, the deterrent effect evaporates. The message to other companies is plain: It pays to break the law.

At a time when authoritarian power is on the rise, we must not forget that plutocracy is also its own kind of dictatorship. That is the danger when we fail to enforce antitrust laws with clarity and conviction — that enormous concentrations of wealth will have too much influence over our lives.

One way to choose your side is to find a community that aligns with your values, and join up. If you agree with what I’ve said above, you might consider my own Creative Good community. You can join here. You’ll get access to our members-only Forum, and all of the Big Tech alternatives listed at Good Reports. And you’ll support my writing here, as I try to tell the truth about what tech is doing to all of us.

Until next time, keep choosing the good –

-mark

Mark Hurst, founder, Creative Good

Email: mark@creativegood.com

Podcast/radio show: techtonic.fm

Follow me on Bluesky or Mastodon